The trial of a retired Australian baker sentenced to 12 years in jail in Vietnam on terrorism charges was a “charade”, his son says, saying he fears his father will die in jail as he faces his final appeal on Monday.

Political prisoner Chau Van Kham, 70, was arrested in Vietnam in January 2019, accused of meeting with fellow members of Viet Tan, a pro-democracy advocacy group proscribed by Vietnam’s communist government, and of helping finance the organisation.

Chau’s single-day judge-only trial, held simultaneously with four other people, saw him tried and convicted on charges of “financing terrorism”, and sentenced to 12 years in jail, all within four hours.

The court was effectively closed – open only for approved people, his family was excluded – for the entirety of the trial.

Speaking at the United Nations’ Geneva summit for human rights and democracy in February, Chau’s son, Dennis, described his father’s 12-year sentence as “effectively a death sentence”.

“The entire charade was rushed and improper. He was assigned a lawyer who was allowed a one-hour session with my father in-person prior to the trial. My father was given one hour to consult with his lawyer after being subject to investigation for 11 months.

“Neither the media nor family members were allowed access to the courtroom. The trial was wrapped in four hours, in what was a wholesale, predetermined verdict. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.”

He said his father’s physical and mental health had deteriorated dramatically over 13 months in prison, and he had been isolated from his family. Dennis Chau said he feared his father could not survive his prison sentence.

“He’s held in a cell for 23 hours of the day with one hour of exercise permitted. We’ve made requests for family visitation, none of which have been granted.”

“My father turned 70 last year, and so with a 12-year sentence, he’ll be 82 when he is released. Factoring in prison conditions and poor access to medical treatments, I don’t believe I’ll ever see him alive, a free man. It’s effectively a death sentence.”

Chau’s appeal against his conviction and sentence will be heard early Monday morning in Ho Chi Minh City. In response to his appeal, the prosecution have added to their indictment a request he be deported from Vietnam after he serves his sentence.

Sources close to Chau say they have little faith in the appeals process, and little hope for a quashing or reduction in his sentence. A US citizen, Michael Nguyen, convicted on identical charges, and also sentenced to 12 years in jail, had his sentence confirmed in a recent appeal.

Chau’s family and supporters say the Australian government needs to more aggressively pressure the Vietnamese government over what they argue is clearly a political prosecution.

He has been allowed one meeting with his lawyer ahead of his appeal.

Previously, Chau had been granted one consular visit a month – always observed by Vietnamese security officials – but Australian consular officials were denied a meeting in February, with authorities citing concerns over coronavirus for cancelling all consular visits for prisoners.

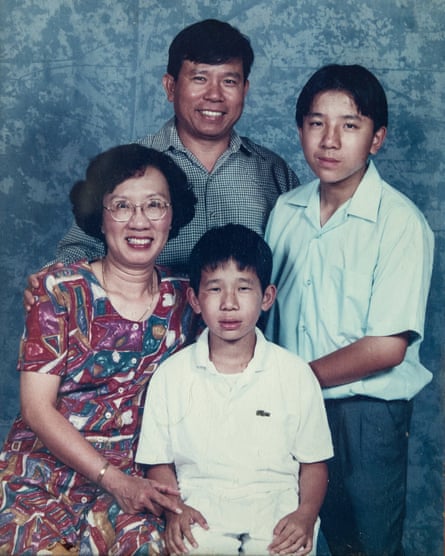

Chau, an Australian citizen, was born in Vietnam and served in the army of the Republic of Vietnam before 1975. After the war, he was sent to a re-education camp for three years, before he fled Vietnam by boat, arriving in Australia in 1983. In Sydney, he worked as a baker for decades, rising before dawn to work at a modest suburban bakery.

In 2010, he became a member of the Viet Tan pro-democracy organisation, and became a key Australian organiser of pro-reform rallies and an outspoken advocate for democratisation in Vietnam.

In the 1980s, Viet Tan had advocated for the toppling of the communist government through popular uprising, but in recent years it has explicitly “rejected the use of violence”, stating the organisation is “convinced that nonviolent means are most effective for generating maximum civic participation … to contribute to Vietnam’s modernisation and reform”.

The United Nations describes Viet Tan as “a peaceful organisation advocating for democratic reform”, but it was formally proscribed as a terrorist organisation by the Vietnamese government in 2016, which said it was “a reactionary and terrorist organisation, always silently carrying out activities against Vietnam”.

Chau sought to return to Vietnam in 2019 to meet fellow pro-democracy advocates but was refused a visa by the Vietnamese government.

He chose to cross into Vietnam via a land border with Cambodia in January, carrying false identity documents.

He was later arrested after meeting with a democracy activist who, it is believed, was under surveillance, along with Vietnamese nationals Nguyen Van Vien and Tran Van Quyen, who were sentenced to 11 and 10 years in prison respectively.

Chau was initially charged with participating in activities aimed at overthrowing the government, but in July this was downgraded to “terrorism to oppose the people’s government”.

Vietnam’s Ministry of Public Security said in a statement Chau was convicted of holding a senior position in the New South Wales chapter of Viet Tan, for “financing terrorism” and for recruiting new members to the movement.

Dennis Chau said his father was a peaceful man, committed to campaigning for a more democratic Vietnam.

“My father came to Australia with nothing but the clothes on his back as a refugee after the Vietnam war. He worked hard all his life to make something for him and his family in his new adopted home. He grew to be a proud Australian, proud of the freedoms we take for granted.

“I feel as though when my father left the land he loved, he left something behind … he felt for the people of Vietnam … he felt compelled to advocate and affect change. He’d never abandon his sense of duty to call for a more open, free society in Vietnam.”

Dennis Chau said he hoped the international community would continue to raise his father’s case as a matter of concern with the Vietnamese government. And he said the Australian government must do more to pressure Vietnam, a significant trading partner.

“The Australian government must be held to a higher standard, as a western democracy, to not put trade relations above basic human rights – the ones that we hold so dear.

“It is silence that breeds inaction. It is silence that lets these governments know that it is OK to continue with their ways.”